- 4 1 F A C B A 3 7 4 A E D 3 0 7

- E 6 5 D 2 C 5 9 1 B 3 4 F A B 0

- A D 7 2 C D 0 4 A 4 C 8 3 B F 3

- 1 3 B C B 5 D 1 5 8 3 0 8 2 5 3

- 9 6 E 6 E 4 E 6 2 3 7 3 8 3 6 F

- 1 6 4 E C 3 D F 2 B 0 4 2 2 2 2

- 0 3 9 A 8 B C 2 4 E A 2 B 1 E F

- 8 C 8 2 2 0 E B 0 2 C B 1 B 2 7

Preamble

Since 2015 I have intermittently worked with Mark Karpov on the venerable megaparsec Haskell package.

With the release of megaparsec-6.0.0, all polymorphic parsing combinators were moved to the newly released parser-combinators package.

Unlike megaparsec, parser-combinators is a fully generic parsing package with a truly minimal dependency footprint!

According to a hackage reverse dependency query, parser-combinators is a direct dependency of 63 packages at the time of writing, so ecosystem adoption is modest but notable.

With the release of parser-combinators-0.2.0 I added the Control.Applicative.Permutations module, and since then my maintenance contributions to both megaparsec and parser-combinators has waned to primarily this sole module.

Despite the module’s small interface, simple type signatures, and succinct code, I greatly appreciate the practicality provided as well as the theoretical underpinnings.

The algorithm I used for efficiently parsing arbitrary permutations of combinators was neither original nor recent work.

Published in 2004, “Parsing Permutation Phrases” describes astonishingly elegant functional definitions for representing and processing permutations.

The work is deserving of the attributed accolade “Functional Pearl”.

A reviewer comparing the Haskell code within the module to the decades old paper would find immediately recognizable similarities as well as a few compatibility modifications required to bring the original work up to the modern Haskell Prelude.

While the correctness and elegance of this pearl will never age, what follows is a meager insight relating permutation parsing and Computation Tree Logic.

Postulate

My present comprehension of and commentary on permutation paring did not manifest from the ether.

The inciting incident emerged as an evidently innocent issue.

A feature request was made for an extension of the parser-combinators package’s Control.Applicative.Permutations module to include the following additional parser combinator definitions:

manyPerm :: Functor m => m a -> Permutation m [a]

manyPerm parser = go []

where

go acc = P (Just (reverse acc)) (go . (: acc) <$> parser)

somePerm :: Functor m => m a -> Permutation m [a]

somePerm parser = P Nothing (go . pure <$> parser)

where

go acc = P (Just (reverse acc)) (go . (: acc) <$> parser)From the same feature request, operational ambiguity was removed by elaborating on the hypothetical usage the new parser combinators.

The permutation parser spec was considered to help better understand the requested parsing semantics:

spec = (,,)

<$> char 'a'

<*> optional (char 'b')

<*> somePerm (char 'c')The feature request expects the behavior of spec to successfully parse the following input/output pairings:

"abc"-

('a', Just 'b', "c" ) "cac"-

('a', Nothing , "cc") "cacb"-

('a', Just 'b', "cc") "cabc"-

('a', Just 'b', "cc")

The last three pairings exemplify how the semantics of the requested parser combinators differs from the existing combinators’ functionality, by “grouping up” 'c' values encountered within the input string and returning the collection of 'c' values in the third slot of the permutation parser’s result.

Permutation Parsers

Persistent problems in perpetual processing

There are going to be some technical problems with parsing permutations under the semantics of the feature request.

Let us consider another parser combinator example and unpack how the permutation parser (currently) works:

Permutation Parser:

example = (,,)

<$> char 'a'

<*> manyPerm (char 'b')

<*> somePerm (chat 'c')Furthermore, let us consider two input strings and outcomes:

Input String:

acceptable = "ccba"

nonhalting = "ccbacbcb"Desired Outputs:

success = ('a', "b", "cc")

failure = ('a', "bbb", "ccc")Alternation Trees

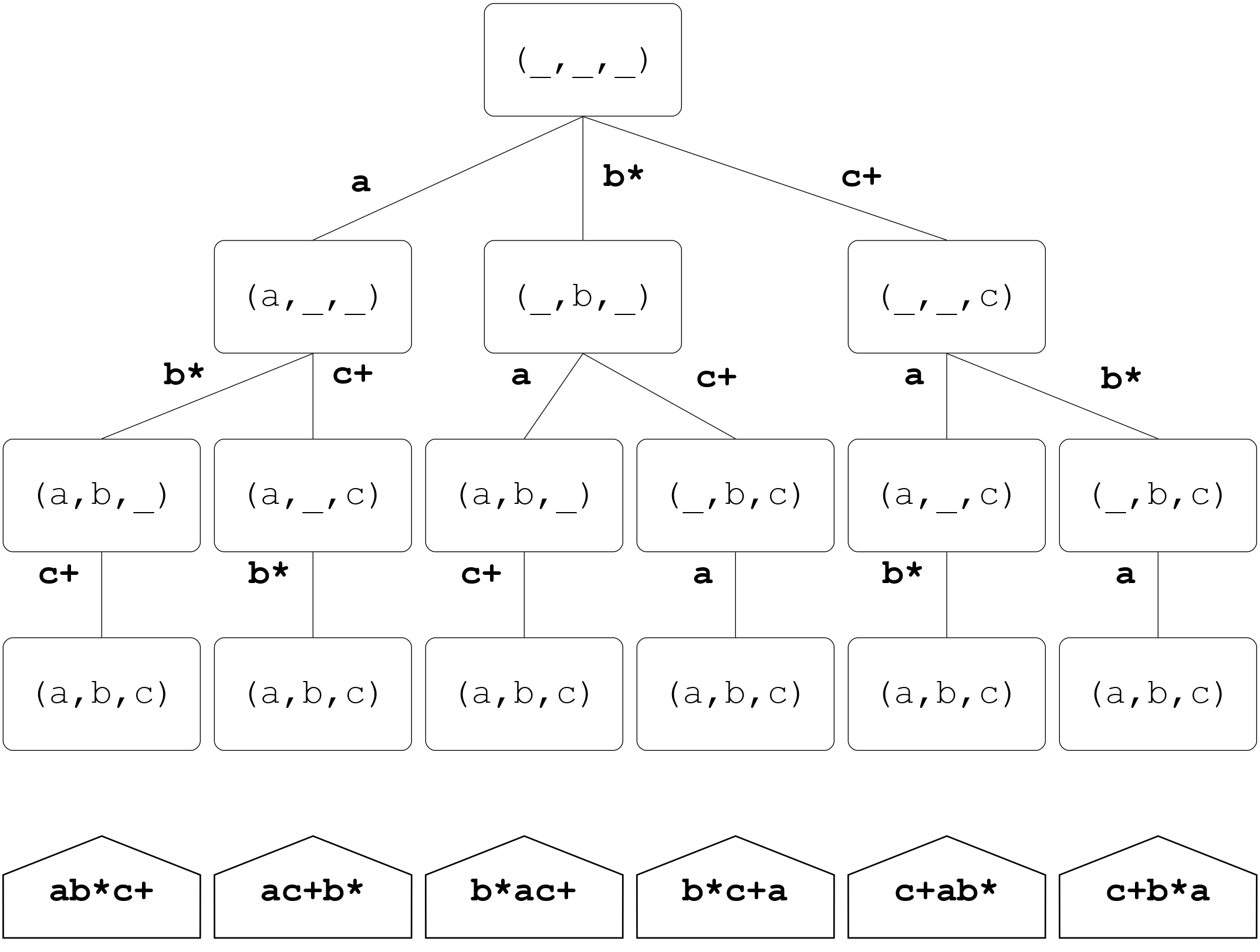

The way permutations are parsed is via a tree structure.

The height of the parsing tree is exactly N, where N is the number of parser combinators used to construct the permutation parser.

For the permutation parser example defined above N = 3.

The number of children at a node is equal to the node’s height.

For the permutation parser example defined above, the root node at the “top” of the tree has 3 children, each of these children on second layer has 2 children, the third layer has 1 child, and finally the leaves have zero children.

Nodes in the tree represent permutation parser state and edges correspond to a successful parse result of one combinator.

Nondeterministic computation

The parser evaluation is best thought of as a nondeterministic sequence of partial computations which occur while traversing the tree in a breadth first, layer by layer traversal, terminating when it arrives at a single leaf node representing a complete permutation. At the root of the tree the permutation parser attempts to parse each of the N possible combinator. The edges leading from the root node to the second layer of nodes correspond to successfully parsing one of the combinators. For each successfully parsed combinator at the root node, the computation follows the corresponding edge to the node in the second layer. Note that not all nodes on the second layer are visited. A parse failure of a combinator means that the corresponding edge to the second layer will not be traversed and the whole sub-tree will be pruned from the computation.

Each node in the second layer uniquely represents the partial computation state of 1 successful combinator parse result. The partial computation at the node contains the result of the permutation combinator which lead into the node as well the partially consumed input stream missing the elements consumed in parsing the associated combinator result. The nondeterministic computation continues on the second level with each visited node independently resuming the partial computation. The nodes attempt to parse the N − 1 combinators remaining, excluding the 1 combinator which has a parse result stored in the node’s partial computation. Similarly to the root node, for each successfully parsed combinator at the node in the second layer, the computation follows the corresponding edge to the node in the third layer. Again, a parse failure of a combinator on the second layer means that the corresponding edge to the third layer will not be traversed and the whole sub-tree will be pruned from the computation.

This form of nondeterministically extending partial computations down a tree, pruning the search space on combinator parse failures continues. Generally speaking, when parsing a permutation with N combinators, a tree of height N is produced. The root node is said to have height N and the leaves are said to have height 0. On the layer with height x, each node contains a partial computation with N − x combinator results from the path to the root node and there are x remaining combinators which must be parsed in the node’s (inclusive) sub-tree. The nodes within the layer with height $$` each attempt to parse their unique set of x remaining combinators, excluding the unique set of N − x combinators which parse results are already stored in the node’s partial computation. For each successfully parsed combinator, the computation follows the corresponding edge to the node in the layer with height x − 1. A parse failure of a combinator corresponding edge to the layer with height x − 1 will not be traversed and the subtree beneath the untraversed edge will be pruned from the computation.

When a leaf node is reached, the height is x = 0 and there are N − x = N unique successfully parsed combinators and x = 0 remaining combinators. Hence reaching a leaf node in the nondeterministic computation terminates the computation with a successful permutation parse result, each combinator being parsed once. The first leave node reached ends the entire nondeterministic computation with a successful permutation parse result. If no leaf node is reached, the permutation parser fails.

The computational tree of example

With the permutation parser evaluation described above, there are exactly 6 regular expressions which will be accepted by the permutation parser example.

ab*c+ac+b*b*ac+b*c+ac+ab*c+b*a

Below is a rendering of the generic permutation parser’s computational tree. The circular nodes show the tuple containing the partial parse result, corresponding to the parser state of the computation. The edge transitions are labeled with indicators of which parser combinator was used to transition from one parse state to the next. Beneath each leaf of the computational tree is a polygon containing the regular expression which the leaf parses.

Note how each path from the root to a leaf corresponds to a unique permutation of example’s component combinators!

Furthermore, the nodes along the path from each root to each leaf produce a unique sequence of partial computations which, when composed sequentially, produce a unique parsing computation for each permutation.

The computation tree, by construction, always terminates.

Performance considerations

With this nondeterministic tree evaluation algorithm, we are certain to successfully parse a constructed “Permutation Parser” if and only if the prefix of the input stream matches a permutation the component combinators. To analyze the performance of this permutation parser construction we will require deploying some graph theory. For permutation parser with N combinators, the graph G = (V, E) results in a computation tree, with 1 root node and N! leaf nodes. The number of edges |E| equals the number of permutations of non-null subsets of N distinct objects. Fortunately, this is a well defined expression documented by OEIS A007526.

edges :: Natural -> Natural

edges 0 = 0

edges n = n * ( edges ( n - 1 ) + 1 )All graphs G = (V, E) which are a tree, have the |V| = |E| − 1. This too is a well defined expression, documented by OEIS A000522.

nodes :: Natural -> Natural

nodes = succ . edgesAdditionally, all graphs G = (V, E) which are a tree, have the a number of paths from the root node to a leaf node equal to the number of leaf nodes.

paths :: Natural -> Natural

paths n = product [1..n]For simplicity, let us assume all component parsers are pair-wise mutually exclusive. Elegantly, the tree structure of the algorithm memoizes partial computations, preventing a full look ahead and full backtracking on permutation parser evaluations which initially succeed on one or more component combinators then subsequently fail on a later combinator. Furthermore, lazy evaluation means that the nondeterministic algorithm does not explore the whole tree. Instead it performs a depth first search with the described early abort/short-circuiting of a subtree if the associated combinator fails to parse. Additionally, because in practice the combinator attempts are evaluated single threaded in the order of composition, a clever author can order the component combinators in order of success probability. The practical result of this algorithm coupled with lazy, single-threaded, order-dependent evaluation is the following:

In the best case, the algorithm will only proceed down one path of the computational tree, with 0 redundant parse attempts of component combinators. Conversely, in the worst case, the algorithm will attempt to proceed down all N! paths of the computation tree, and at each leaf node of each path (except the last path) have the associated component combinator fail to parse, resulting in |E| − N redundant parse attempts of component combinators (wasted work). Hence we have the parsing algorithm bounded below by Θ(N) and above by O(N!).

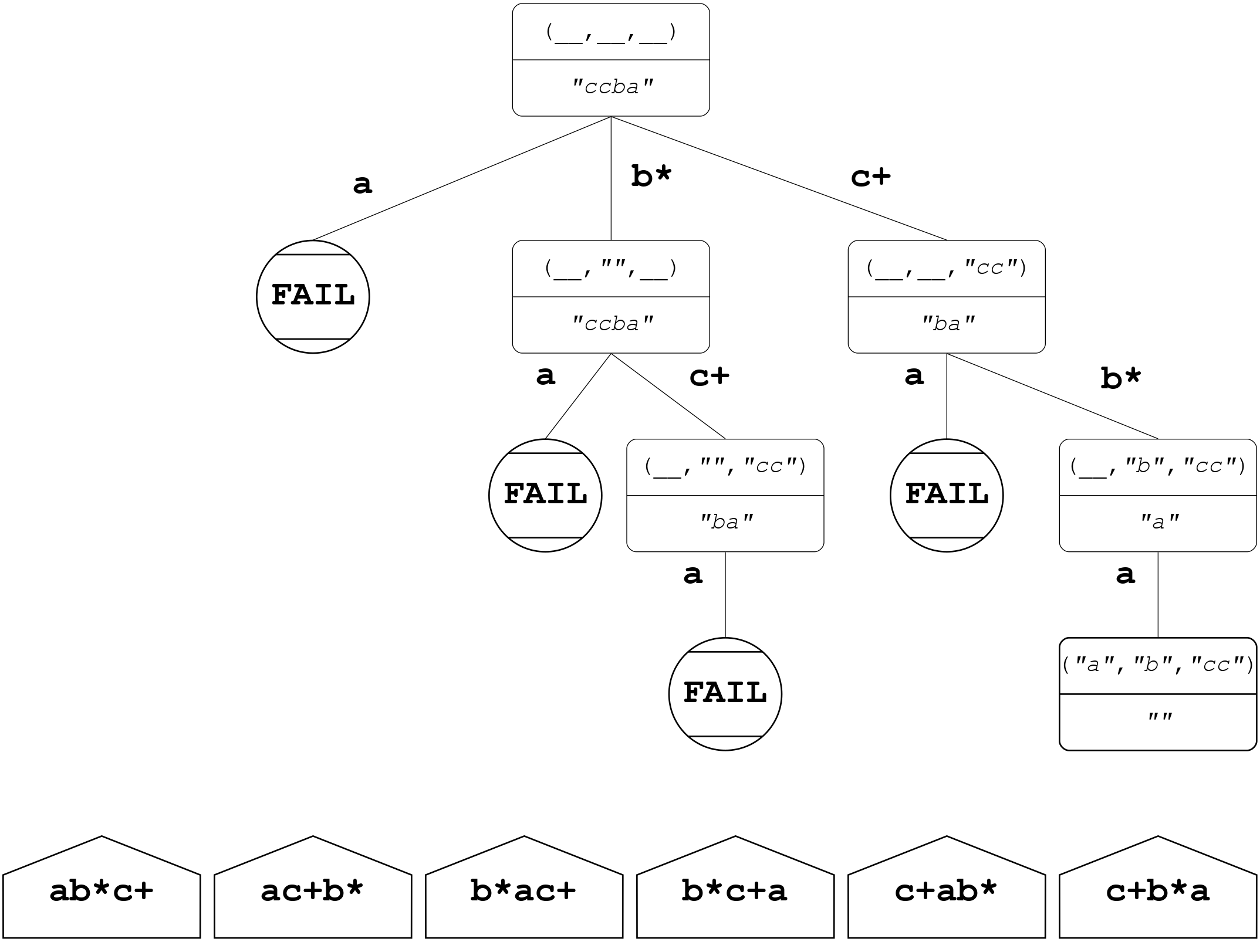

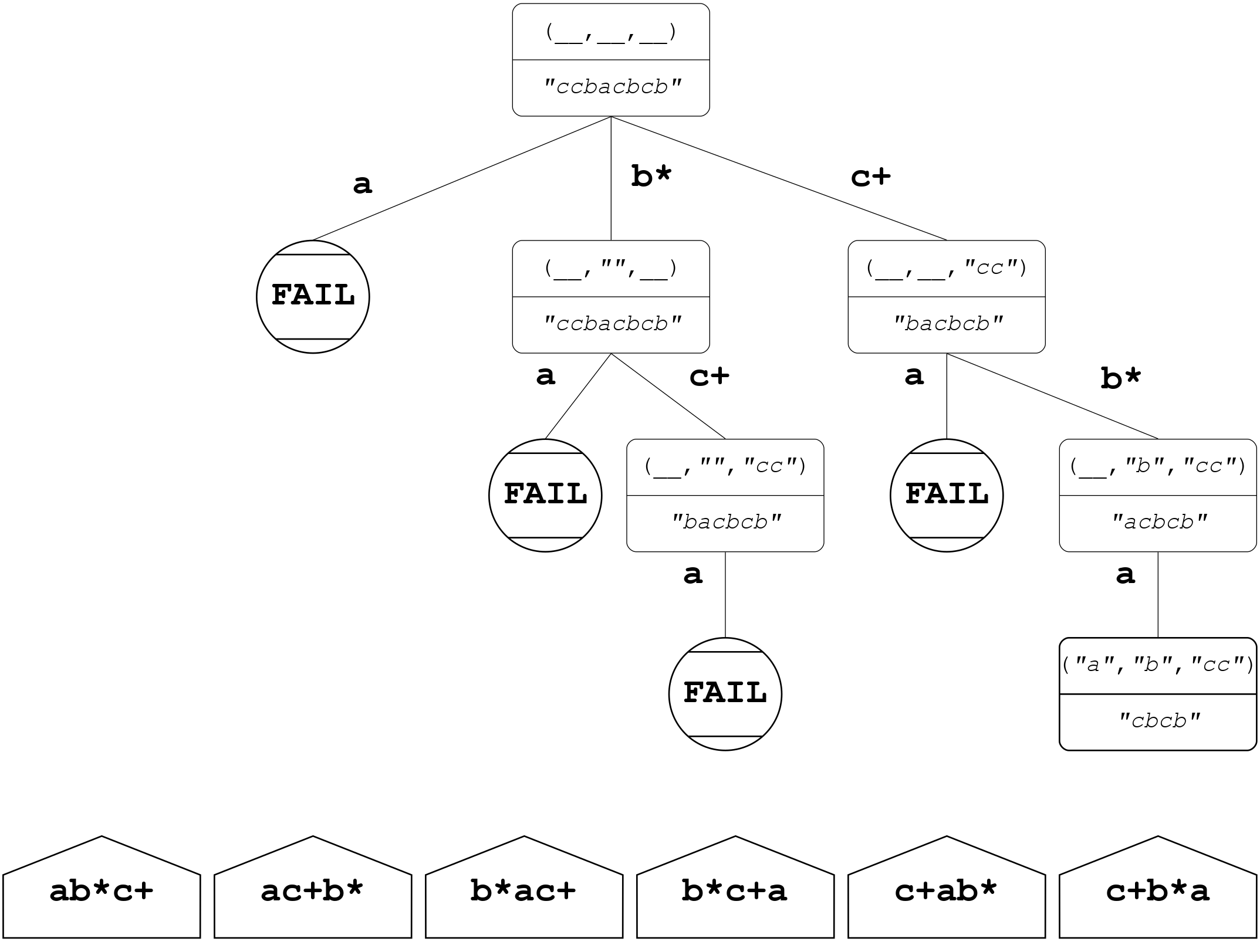

Picturing parse processes

Below are renderings of permutation parse trees of partial computations for example on two inputs.

They illustrate the search graph of the permutation paring algorithm and facilitate tracing steps through the search space.

First, consider the acceptable input string, desiring the output to be success:

>>> parse example acceptable

Right ('a', "b", "cc")

>>> parse example acceptable == Right success

TrueIn this case, example succeeds in parsing the specified permutation, resulting in success while also consuming the entire input string.

This is exactly what was desired, and hopefully also what the reader would expect.

Next, consider the nonhalting input string, desiring the output to be failure:

>>> parse example nonhalting

Right ('a', "b", "cc")

>>> parse example nonhalting == Right failure

FalseHere we can see that the permutation parser example “succeeds” in parsing nonhalting, but the result leaves in the unconsumed suffix many of the stream symbols the proposed combinators permMany and permSome were desired to match.

This occurs because the permutation parsing algorithm dismisses a component combinator after a match, and never again considers it for the remainder of the input stream parsing.

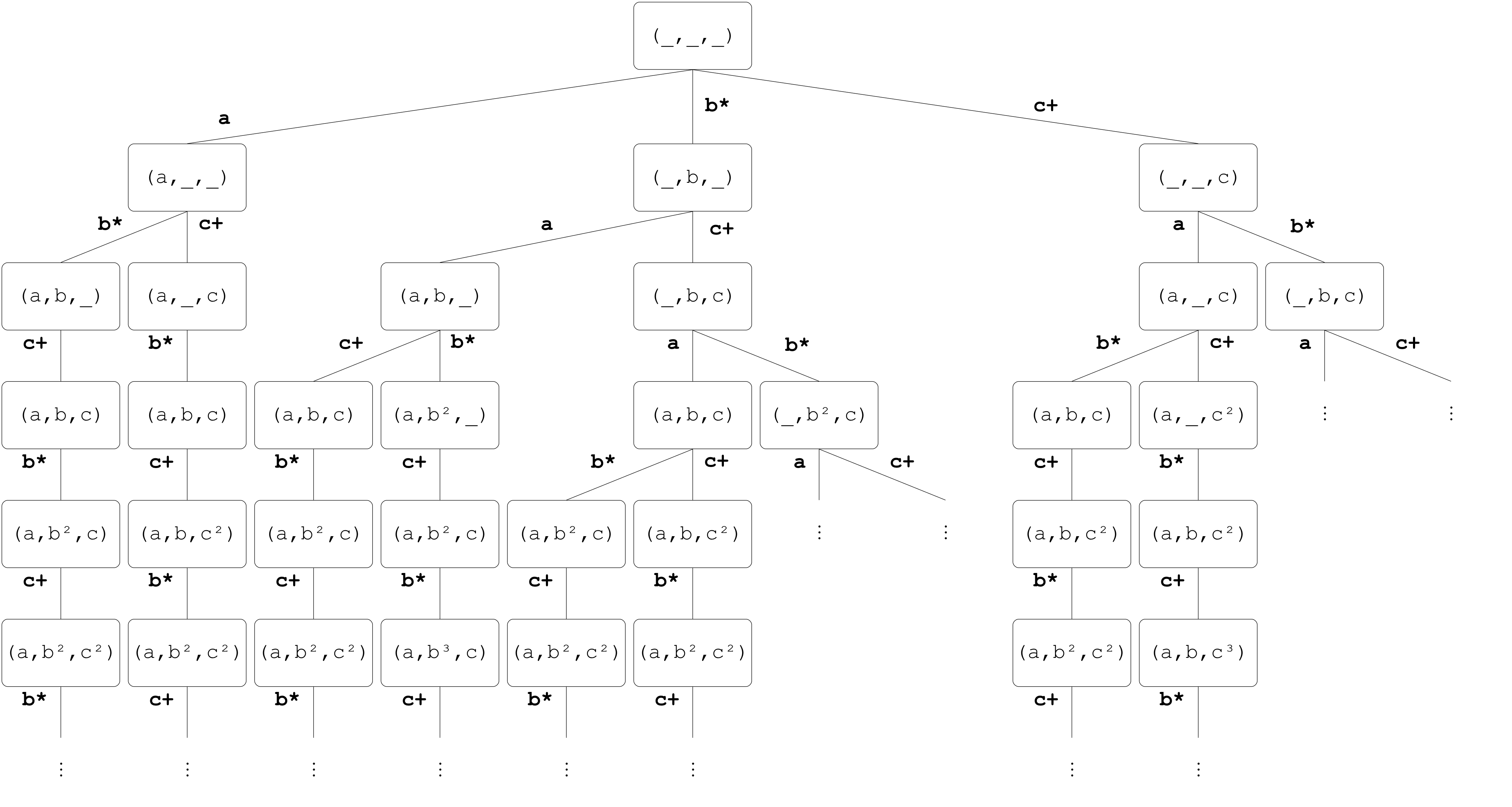

To modify the algorithm to support the desired semantics of permMany and permSome we would need to construct a new computation tree which, as the nondeterministic computation progresses, preserves all composite combinators which are either permMany or permSome definitions.

Let’s visualize what such a computation tree would look like for example.

Modified computational tree of example

Below is a partial rendering of a computational tree which yields the requested semantics for permMany and permSome.

Likely the first noticeable feature of the computation tree is that it is infinite.

Any permutation parser containing permMany or permSome will necessarily produce a computation tree containing an infinite recursive progression of branching subtrees.

Recall that the evaluation algorithm for a permutation parser requires exploring all possible branches until each combinator is successfully matched or a parse failure occurs.

By the desired semantics of permMany, it can only result in a partial success which awaits another matching input, or a parse failure.

Similar reasoning holds for permSome.

Hence, permMany and permSome will always result in either a parse failure or an infinite loop (only possible when parsing an infinite stream).

This is why the desired semantics for permMany and permSome will produce an infinite computation tree.

Conclusion

Any permutation parsed constructed with

permManyorpermSomeand evaluated as described by “Parsing Permutation Phrases” will evaluate to eitherfailor ⊥.